When Madison was a student, at what is now Princeton, he stayed another year to work on a study of the world's constitutions while soaking up the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment from the university's president. This began his life-long passion for republican ideals and constitutions. After flailing about for a while after college, he was elected to the Virginia (Colonial) House of Burgesses and began his life as a politician. He followed this calling to public service until the end of his presidency. Those who call for term limits and hold their noses at the idea of a "politician" could learn a lot from his decades of devotion.

After the Revolution, he watched with mounting horror as self interest brought out the worst in the Virginia legislature and the Congress under the Articles of Confederation was worse than "do nothing." By 1878, the country was in turmoil, Congress was impotent, groups of States talked of leaving the fragile union spurred on by European powers, the economy was a shambles, and Shays' Rebellion in Massachusetts frightened every property owner. The prognosis for continued existence of the country was dire.

So Madison joined Alexander Hamilton and Ben Franklin to conspire to overthrow the government; they committed treason for the second time. Working with others, Madison persuaded General George Washington to join in the call for a Constitutional Convention to provide the political cover they needed. Madison got the resolution through the Confederation Congress and became a delegate along with Washington and others to the gathering. His long-time rival, Patrick Henry, refused to have anything to do with it; "I smell a rat!" He was right, of course. Madison's intent was not to amend the Articles but to abolish them.

|

| Jemmy and Me |

He arrived in Philadelphia early, having made a thorough study of republics and constitutions "ancient and modern." He persuaded the governor to present his draft as the "Virginia Plan." Although little of it remained in the final draft signed by the delegates, it did serve as the agenda and shaped the nature and substance of the debates. Madison and the most committed delegates toiled for four months in the Philadelphia summer heat with early morning committee meetings, all-day debates, and informal politicking in the evening. Madison took voluminous notes we still marvel at today and early Supreme Court justices used to unravel "original intent."

But when the delegates scattered back to their states, the work wasn't over. They had to get the special ratifying bodies to agree to the document. In Madison's Virginia, Patrick Henry led the anti-federalist forces. Despite Henry's legendary oratorical skills and political clout, Madison bested him and eked out a tiny margin of victory.

Then he was off to the new Congress as a Representative in the House and to serve as Washington's whip in that body to achieve his legislative agenda. He served as Jefferson's Secretary of State and then as President, presiding over the War of 1812. In fact, he was the only Commander in Chief to actually go into battle, despite having no military credentials.

He was the last of the "fathers" to depart this world and did so on this day, June 28, 1836. His parting words were, "Nothing more than a change of mind, my dear." James Monroe, who succeeded him as President, referred to Madison in his dying words, "I regret that I should leave this world without again beholding him."

In my Google Alert for Madison, about 95% of the mentions are from people, right or left, trying to claim his "authority" for their views. Like anyone quoted out of context, Madison's words are distorted. More importantly, because Madison was a patriot, a passionate politician, and as partisan as anyone, you can always find some snippet to support you. These folks do a disservice to the man, his memory, and his message.

Madison, like all of us, evolved and changed with age. At the end of the Convention, he thought the Constitution was a failure because it created a Senate representing the states and not the population. Yet he went to the ratifying convention and worked with Hamilton to write the Federalist Papers defending the new Constitution with every ounce of his considerable persuasive talent. By Washington's second term, he had joined Jefferson to destroy Hamilton and the Federalists and create the Republican Party (precursor of today's Democrats.) As president, he opposed legislation for building roads and canals or providing "charity." As an elder statesman, he made it clear he had evolved to support these government efforts.

What made Madison so great was he was NOT an ideologue. He constantly thought about things, changed his mind, and made it clear where he stood at any moment. He was prepared to compromise for the good of the nation. He seldom held real animosity for his opponents. (Today he'd be derided as a flip-flopper, drummed out of whatever party he was in, and excoriated by the chattering class and talk radio.)

What I've always found so appealing about Madison was his humanness. My favorite quote from him is (out of context, of course,) "If men were angels, no government would be necessary." Madison is great because he is no saint on a pedestal. He was dead wrong on many things. He made no claims to perfection. We can admire him, not because we agree with him or can find some phrase to prove our political point, but because he thought continuously and was willing to change and grow and leave old notions behind.

If today's leaders, whether in politics or business, would spend a little time with "Jemmy, the great little Madison," they might be less inclined to require unthinking adherence to a static idea. Madison's interpretation of the republic's mission statement, the Preamble to the Constitution, matured and morphed over time. If we could take a page from his book, we might all succeed in evolving, being more strategic, making better decisions...and leaving old ideas behind.

* * * * *

(c) Rebecca Staton-Reinstein and Advantage Leadership, Inc.

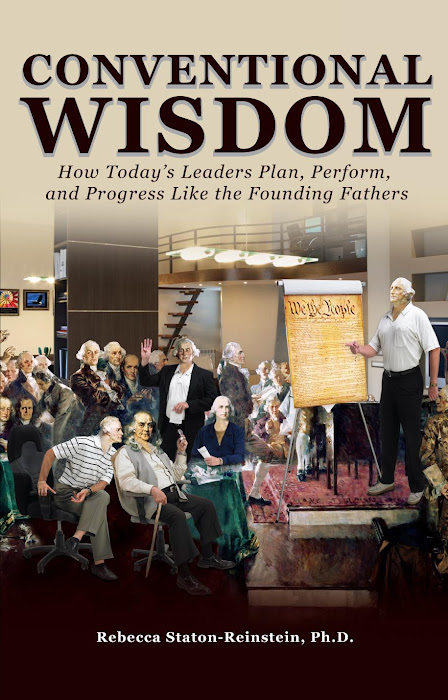

Want to know more about Madison and his role in the Constitution and early republic? Want to know how modern leaders exploit the Madison Factor? Check out Conventional Wisdom: How Today's Leaders Plan, Perform, and Progress Like the Founding Fathers.

Your research into the planning sessions of the Constitutional Convention and the struggles that our framers of the Constitution faced has been cleverly weaved into the strategies of modern business. I am pleased to have your book.

-- Justice Sandra Day O'Connor (RET)