Historical references pop up in the darnedest places. Today’s New York Times (Dec. 31, 2008) profiled the current crises facing Georgia’s president Mikheil Saakashvili and discussed the pressure on him to stand down from some of the power he had accumulated during his tenure.

“Last week, he announced a constitutional amendment that would lessen the president’s power over Parliament. Lately, he said, he is [more] attracted to the model of…George Washington, who, he said, ‘could have been a king, but instead chose to give up power, and become a democracy…It’s something I’m thinking about more and more,’ he said. ‘George Washington.’”

Powerful leaders, whether in government, private industry, or even the nonprofit world, could certainly benefit from thinking more about George Washington and his relation to power and leadership.

For those who may not remember it, George Washington, took on leadership roles from an early age. In the beginning, he wasn’t necessarily very good at it. But he learned from his experiences, from observing both strong and poor leaders, and from wide-ranging reading. He set himself on a self-directed path of improvement, with high standards and clear goals.

By the time he came before the Continental Congress to resign his commission at the end of the American Revolution, he had perfected a leadership style that won loyalty from his troops and admiration from the public. He was not without his critics, of course, who pointed out his all-too-human failings. But when George III heard that Washington had retired from his military command without seizing power in a military coup or allowing himself to be elected king, he remarked that he must be the greatest man in the world.

At the end of his second term as the elected president, not king, he walked away from power again, despite a faction that would have elected him king for life.

Washington presents many object lessons for modern leaders…not the least of which is knowing when to limit one’s own power. Dictators and dictatorial executives and managers are eventually toppled. True leaders know when it’s time to step back or even pass the torch.

Wednesday, December 31, 2008

Saturday, December 20, 2008

Did the founding fathers support smaller government?

Folks often want to find support for their contemporary views by citing our U.S. founding fathers, something like folks quoting from sacred writing. The problem is that the ‘fathers and mothers’ did not share a monolithic point of view as documented in their public and private writings.

I was struck by this recently when I read an otherwise thought-provoking opinion by Carly Fiorina in the Wall Street Journal December 12, 2008. (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122904246460000265.html#printMode) It was entitled “Corporate Leadership and the Crisis: CEOs seeking bailouts should be willing to resign.”

Although I agree with much of what Ms. Fiorina said in her article, citing the Founding Fathers as supporting smaller government was off the mark historically.

In fact, the founders and framers of the U.S. Constitution had serious disagreements about the extent of government. And, some of them changed their views over the course of time. For example, when James Madison and Alexander Hamilton allied with others to call the Constitutional Convention of 1787, they both envisioned a strong national government to replace the supreme power of the states under the Articles of Confederation.

A few years after the Revolution, the weak confederation was collapsing under its own weight. Madison's statement on government applies as well today as it did over 200 years ago: "But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary."

Madison and Hamilton argued forcefully, writing as Publius in The Federalist, for the supremacy of the new national government. Hamilton would have gone further and abolished the states themselves according to his critics.

By Washington's second term as President, Madison had moved away from his more nationalist stand and allied with Thomas Jefferson to found a political party to tout the need to have more power in the states and to lobby for smaller national government. When Jefferson defeated John Adams in the 1800 election, he proclaimed a second Revolution and tried to undo as much of the Federalists' initiatives as possible.

As the parties morphed, evolved, disappeared, and sprang to life over our history, they all tried to claim the founders and framers as their own. The truth is somewhere else. The tension between the states and the federal government was built into the Constitution because the framers understood they could never get agreement on a perfect system.

The so-called Great Compromise of the convention was about how states would have power in the new system. The fault lines run directly from the convention to the civil war and on into today.

Essentially, we have agreed to disagree, just as the founders and framers did on how much power government should wield at each level, how big government should be, and how the checks and balances of a republican system should work.

Indeed, we are not angles and our system of government reflects accurately on our human nature.

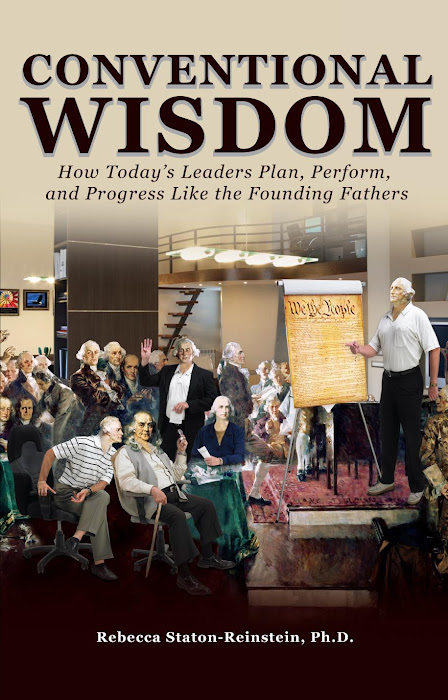

Want to know more about what the founders and framers were really thinking and how it relates to contemporary strategic leadership questions? Conventional Wisdom: How Today’s Leaders Plan, Perform, and Progress Like the Founding Fathers will be published by TobsusPress at the end of January 2009. Check out the website for pre-publication offers. http://www.advantageleadership.com/conventional-wisdom.html

I was struck by this recently when I read an otherwise thought-provoking opinion by Carly Fiorina in the Wall Street Journal December 12, 2008. (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122904246460000265.html#printMode) It was entitled “Corporate Leadership and the Crisis: CEOs seeking bailouts should be willing to resign.”

Although I agree with much of what Ms. Fiorina said in her article, citing the Founding Fathers as supporting smaller government was off the mark historically.

In fact, the founders and framers of the U.S. Constitution had serious disagreements about the extent of government. And, some of them changed their views over the course of time. For example, when James Madison and Alexander Hamilton allied with others to call the Constitutional Convention of 1787, they both envisioned a strong national government to replace the supreme power of the states under the Articles of Confederation.

A few years after the Revolution, the weak confederation was collapsing under its own weight. Madison's statement on government applies as well today as it did over 200 years ago: "But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary."

Madison and Hamilton argued forcefully, writing as Publius in The Federalist, for the supremacy of the new national government. Hamilton would have gone further and abolished the states themselves according to his critics.

By Washington's second term as President, Madison had moved away from his more nationalist stand and allied with Thomas Jefferson to found a political party to tout the need to have more power in the states and to lobby for smaller national government. When Jefferson defeated John Adams in the 1800 election, he proclaimed a second Revolution and tried to undo as much of the Federalists' initiatives as possible.

As the parties morphed, evolved, disappeared, and sprang to life over our history, they all tried to claim the founders and framers as their own. The truth is somewhere else. The tension between the states and the federal government was built into the Constitution because the framers understood they could never get agreement on a perfect system.

The so-called Great Compromise of the convention was about how states would have power in the new system. The fault lines run directly from the convention to the civil war and on into today.

Essentially, we have agreed to disagree, just as the founders and framers did on how much power government should wield at each level, how big government should be, and how the checks and balances of a republican system should work.

Indeed, we are not angles and our system of government reflects accurately on our human nature.

Want to know more about what the founders and framers were really thinking and how it relates to contemporary strategic leadership questions? Conventional Wisdom: How Today’s Leaders Plan, Perform, and Progress Like the Founding Fathers will be published by TobsusPress at the end of January 2009. Check out the website for pre-publication offers. http://www.advantageleadership.com/conventional-wisdom.html

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)